Questions On is the video interview format created by C41. It consists of three simple questions addressed to our network of friends, partners and creative minds. This series will go through Printed Narratives, questioning the role of contemporary publishing in the digital era. This episode features Alba Zari, a cosmopolitan visual artist and her lifelong project The Y, published by Witty Books.

How was the project born? Is there art without life (and vice versa)?

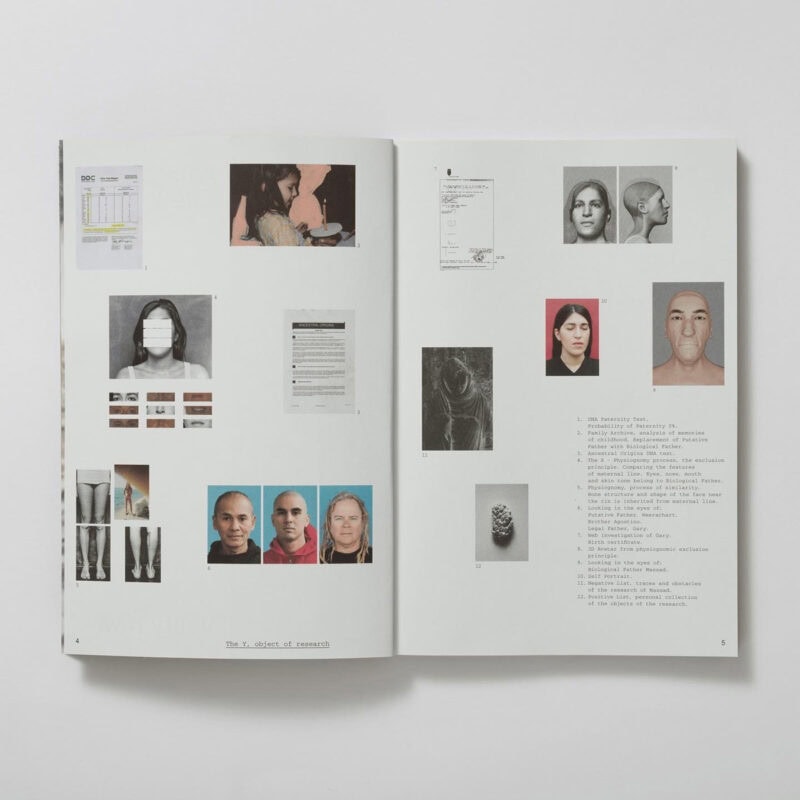

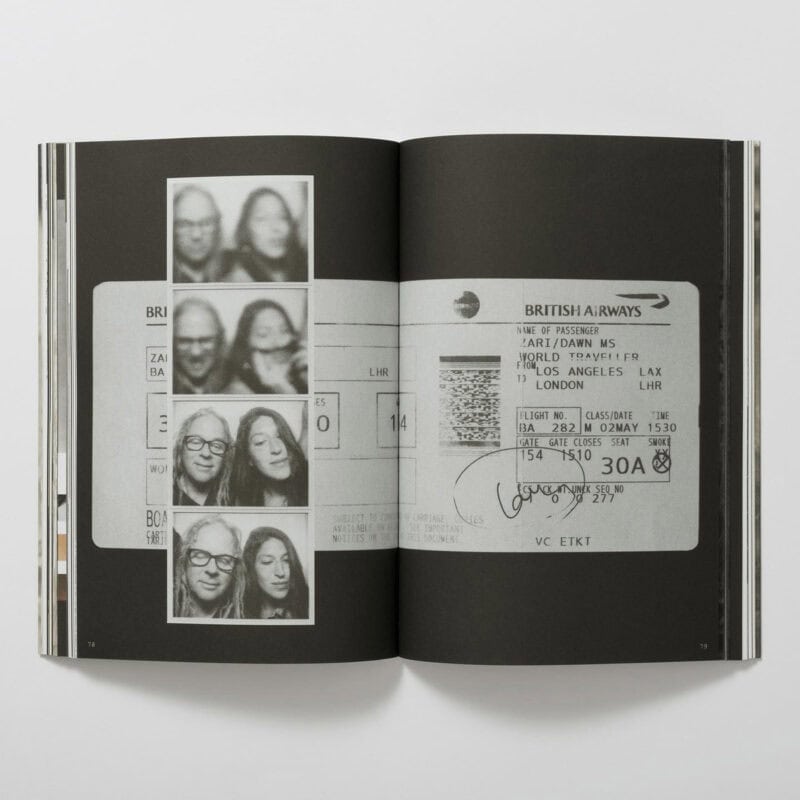

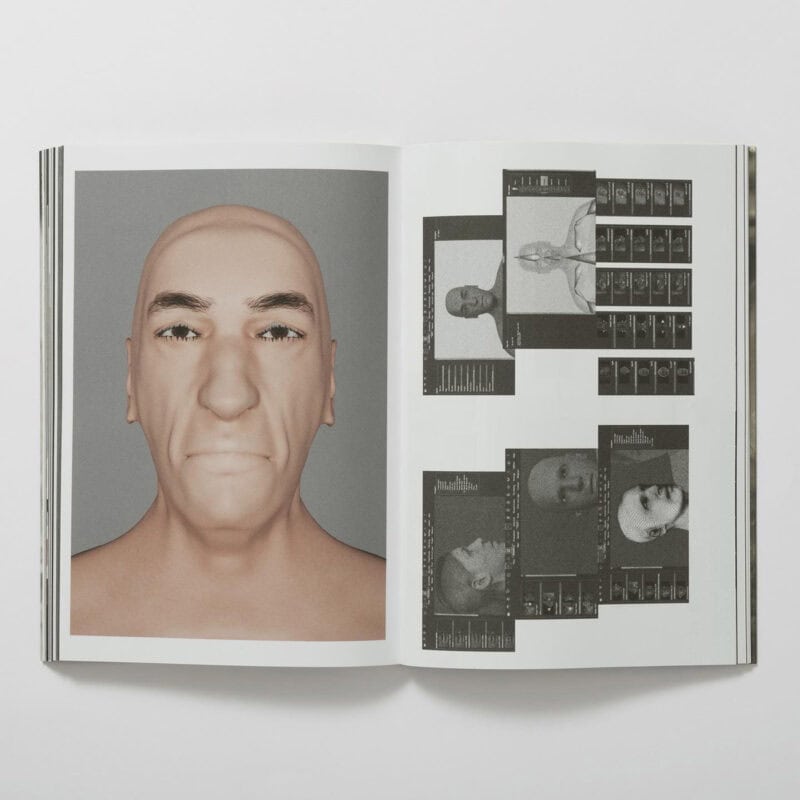

My project called The Y was born out of a research about my father. I never met my biological father so the origin of this story is me looking for him. I thought, from my life, that I was born in Thailand and I had the same father of my brother, and that he was Thai of course. When I was 25 I found out that my real father is unknown, so I decided to have an investigative approach to look for him, also to have emotional distance from such a personal topic. I tried to think about what was important also for the people, what could be in a way universal, so I started to collect documents and chase his identity on myself. The DNA test was the first step I did to the father of my brother to have proof that he’s not actually my biological father. Then I did a test on my ancestral origins and that’s why this project is called The Y: because the Y chromosome is the male one, and that’s the one that can reveal the origins in the DNA – in this case of my biological father, whose identity I wanted to find out. I got pictures of him, and I constructed him. The approach was really analytical and scientific. Then I did physiognomic studies on myself: I used myself to find pieces of him within me, cause I didn’t have any other information then – just his first name that is Massan, and that he could probably be from Milan or Iraq. So, without anything else, I just had myself to try to find him. In fact, I did it; all of my researches didn’t end how I hoped it could end – finding him – and the book finishes with a self-portrait with my eyes closed, accepting the idea and the fact the maybe I will never find out who is he really is. The book is, in a way, a natural consequence of the chronological process of me collecting all the documents and information. I started this project as a book in the first place because it’s a catalogue, it’s processing all the information, it’s putting everything in order and having really a clear overview, a clear space. You can imagine this, being such a personal and difficult journey, it was also really chaotic. Having the idea of putting everything in a place, in order, and looking at the things again, naturally became a book. And of course, that was really very important to me.

Photography is a way to capture reality, but in the end you never truly own it. Is identity an illusion too?

Especially with this project, I really thought about photography and the truth about believing in an image. Especially when I used these pictures, where I have this person that I thought was my father and he really wasn’t, I tried to think about how you can really believe in that picture almost like a fact, that is a testimony of that precise moment – that could be a birthday or a happy memory in the family archive, but those pictures were lying to me. So, in a part of this project, I painted on these pictures a pink silhouette to think about how that person does not represent reality, and how that picture is not true and the person that I wish was next to me on my birthday neither. I was celebrating special moments without even really knowing his identity, so I don’t think that photography can capture reality – I don’t think anyone can capture reality. In such a thing that is not capturable, you cannot prove it and, especially with photography, you can have a point of view – and that can be very subjective (generally I don’t believe in objectivity). Well identity, related to the topic of reality and truth, I think it’s a topic that is as well very flexible and very not a hundred per cent certain. You can believe, you can hope to have a certain type of identity, but in the end it’s just an illusion. Especially when I did like the ancestral origins, it showed that I have parts of me that were from Minnesota, but I also was Irish, Polish, etc. You can think to belong to a certain country, a certain Nation, but I don’t think it’s a… Yeah, it could be an illusion, it could be a way that you think about yourself that makes you strong. You say «I’m Italian», «I’m British», but maybe it is an illusion. I never thought about it in a certain way. But I think, especially nowadays, you cannot be so strong on your identity. You have to be easier about where identity is going, especially in the future.

Publishing could be seen as an anachronistic practice. Why do you think it could still have a role in shaping contemporary visual culture? Is printing a way to return images to where they belong?

Publishing today is very… I still believe is very important. If we think of the way in which we are collecting images on our phone: they can be a lot and we’re not giving importance to them – they’re not precious anymore. The act of publishing and choosing the type of paper, the bonding and making them really precious object is still very important and it’s something that is contributing to contemporary and visual culture for sure. I don’t think printing it’s a way to return images to where they belong: I think it’s a way to create a different meaning and understanding for these images, to make other people look at them. They can project what they’re passing, their own story, so the images become something else and something that belongs to everyone. That’s the reason why is very important to keep on publishing and to make the images become material.

Credits:

Featuring: Alba Zari

Curated by Robin Sara Stauder

Editor: Alice De Santis

Visual: C41.eu