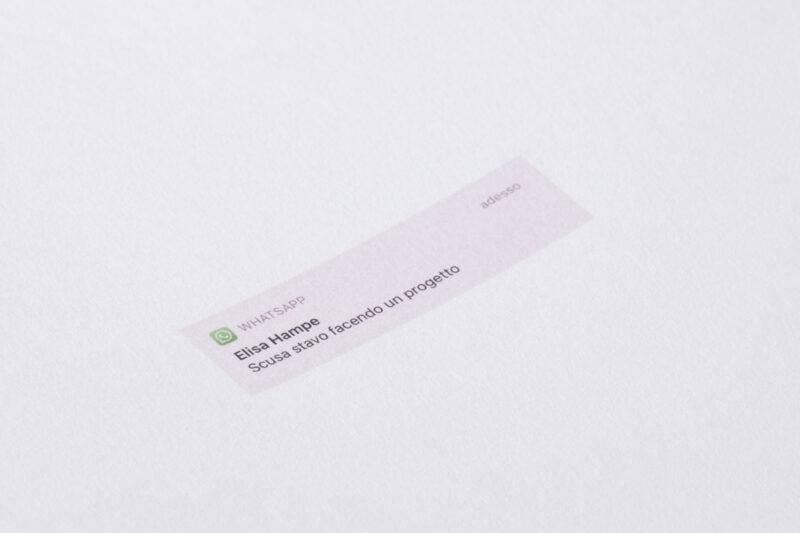

Questions On is the video interview format created by C41. It consists of three simple questions addressed to our network of friends, partners and creative minds. This series will go through Printed Narratives, questioning the role of contemporary publishing in the digital era. This episode features Elisa Hampe and her project ‘Scusa stavo facendo un progetto’.

Elisa Hampe was born in 2001 in Milan. During her childhood and adolescence, she lived in a small provincial town surrounded by greenery, and thus acquired her interest in plants and flowers. She graduated from art school, which gave her a taste for interdisciplinary contamination. Her main medium remains photography, which she is studying at the IED in Milan.

About Scusa stavo facendo un progetto – words by Elisa Hampe:

The project deals with the theme of rest and the corruption of it by means of guilt senses.

Two particular senses of guilt are outlined: that of not making full use of time (the result of the consumerist mentality and exacerbated by the idealised vision of life promoted by Instagram stories), and that of not always being available for others, of not responding immediately to messages.

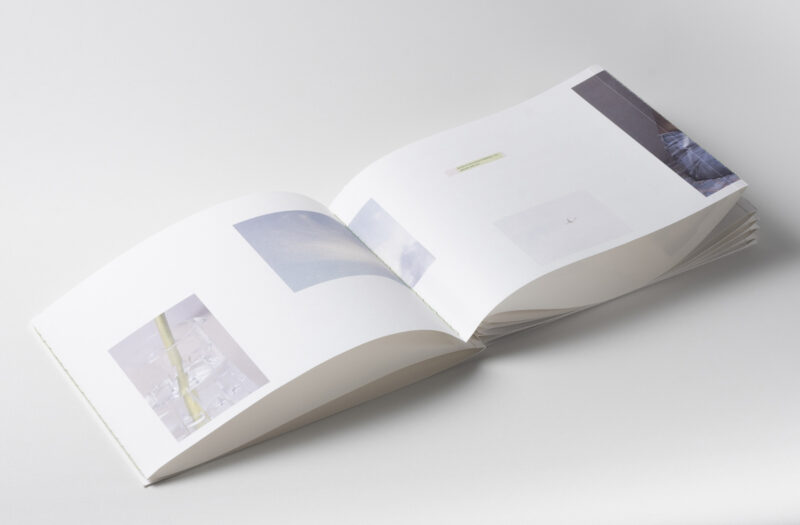

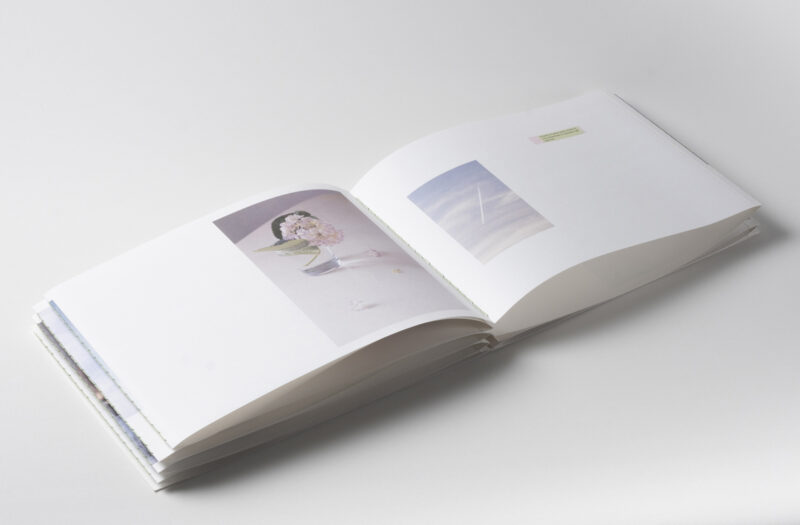

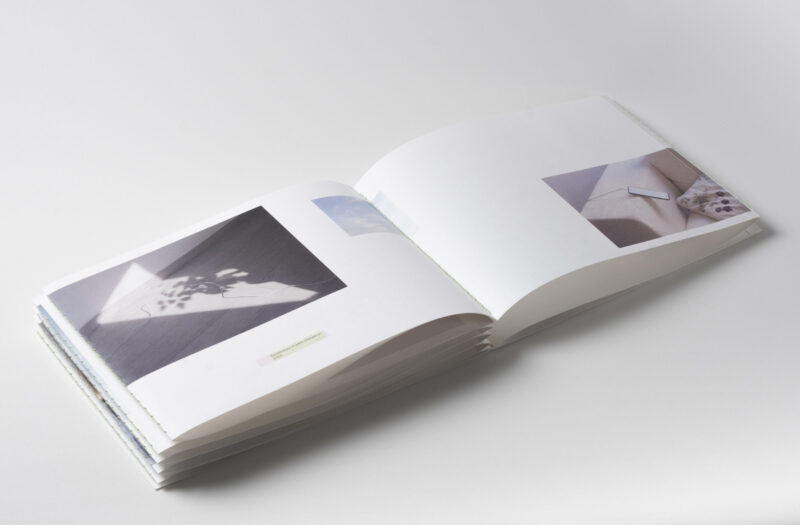

The project is developed along three intertwining narrative lines: screenshots of conversations in which the artist apologises for basic needs; photographs in which he investigates his personal relationship with the telephone (self-portraits, the exchange between inside and outside, looking through a filter prevail); and finally clouds, which, like the images on social networks, are visible to everyone.

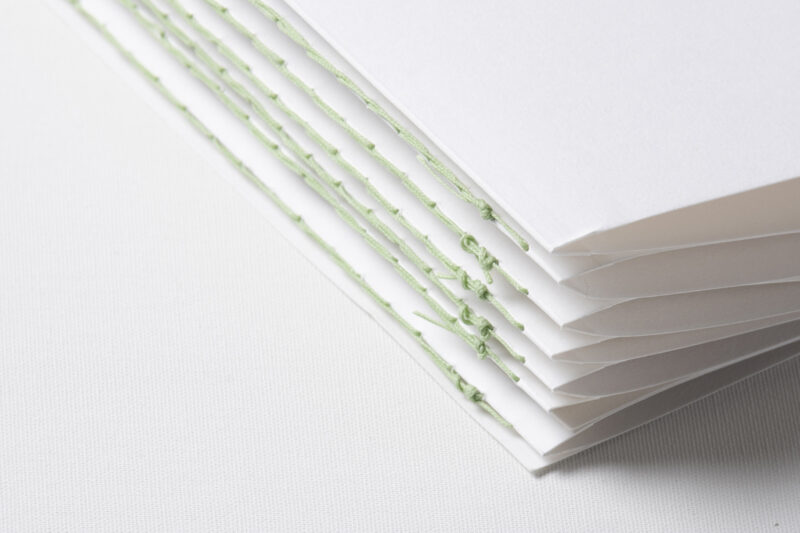

The print format is a continuous line that echoes Instagram stories, but at the same time denies them thanks to the hand-stitching that holds the pages together: a slow, manual process that contrasts with the automatism and speed of social networking.

What is frenzy for you? Why doing nothing today makes us feel guilty?

I mean frenzy as a way of living and thinking, which consists simply in wanting to achieve as many goals as possible in as little time as possible.

In my opinion, it can be traced in every aspect of life. From work, where it’s also easier to recognize it and where it can also be healthy, in my opinion, to want to achieve goals, to want to strive, even if you always tend to set unattainable standards. But above all, it is harmful and more difficult to recognize in the private sphere. Because, for example, when we have a moment of rest, in which in theory we should be free to do nothing, the first impulse we feel is to pick up the phone, go on Instagram and look at the stories of our friends, or maybe even people we don’t know, we just follow. And maybe we don’t care about their lives, but we see what they are doing, we see that they are at the beach, that they are in the mountains, having an aperitif, with friends, and we are at home doing nothing, we feel guilty. And that’s because even in rest, you always have to find a way to be productive.

Even this whole culture of self-care that has developed in recent years, on the one hand, preaches rest, taking care of ourselves, but on the other hand, it also imposes rules that we must respect. If you look at one of the classic lists of self-care routines, what do we find? We find taking a warm bath with candles, baking cookies, walking in nature. There are always rules to follow because simply doing nothing is not contemplated, because if I am not doing anything productive then I am useless.

Time is the protagonist in your project. Was photography a way to stop it or to make peace with its inexorable flow? And what about the screenshots?

My vision of time is closely linked to my vision of life, in the way that I see both as flows, currents, in which we are transported, but which we can suspend momentarily. This can be done by performing actions that can remove us from this concrete space-time dimension in which we find ourselves. And they can be, for example, reading, watching a movie, but also looking at the phone, opening Instagram and seeing images of places far away from us, talking to people who are not physically with us.

There is a difference, however, between reading and watching a movie and looking at the phone: simply in the fact that the first two actions are conscious, that I decide to put myself there and read a book; instead, the phone has become almost a nervous tic, at least for me, that I find it in my hands and then I start surfing the internet and my mind is distracted, I am torn from this flow of life and go into another.

That becomes a distraction, it becomes like when you’re trying to read, and you’re constantly being distracted by something else, and it becomes frustrating.

Especially, I feel this way when I receive messages, which for goodness’ sake people don’t do it maliciously, on the contrary, and I know this, however, I get a message and I have to reply, I have to talk to someone who is not there and get out of the moment I am living in. And I can decide to ignore the message, but I feel guilty.

Then I realized about the screenshots that I have also included in my project, those same screenshots were how I realized, looking at the chat, how often I apologized for not having replied because I was doing something else, but something else such as sleeping, eating or otherwise basic needs that there is no need to apologize.

So yes, maybe it is from the chats that all my thinking started.

As far as my relationship with time is concerned, specifically in photography, you could say that I try to stop time. But it’s not so much a matter of capturing the moment like Cartier-Bresson, that strand of photography. It’s more a matter of trying to cancel time, finding these visions, looking for them in the world around me, or constructing them, in any case, these images that almost deny time and have a sort of aura of suspension, almost as if they were floating.

Publishing could be seen as an anachronistic practice. Why do you think it could still have a role in shaping contemporary visual culture? Is printing a way to return images to where they belong?

In my opinion, printing is very important, especially for those who do a job that is now mainly digital and no longer could physically touch what they are doing.

As a photographer, working digitally at least, I always see everything behind a screen, there is always a glass between me and what I’m doing.

In a certain sense, I think this is alienating because it’s as if the work I’ve been doing for days, weeks, months, never tangibly takes shape. Also, because the speed with which an image appears on a screen is the same speed with which it then disappears.

This in my opinion is absurd, again linking back to the Instagram talk, because when you upload an image on Instagram, you upload it, there’s that hour or two hours of rush and likes where you feel great and then what’s left? The image is forgotten immediately, it stays on your profile, but no one looks at it anymore, no one cares.

It’s very interesting to me to see how social networks have given us the possibility to show our work, what we do to many people, but have deprived us of permanence, of doing things that remain.

I see printing as a reappropriation of the physical space that we no longer occupy.

I see printing as a reappropriation of that physical space, it’s like declaring that I deserve to occupy space, that my work has value.

And I think this is also the reason why, more and more, there is this countertrend to digital, there is this desire of people of my age, who were born with digital, to go back to analog, to go back to shooting on film, to listen to music on vinyl. And it’s very interesting this way that digital and analog weave together, which I think will develop in an increasingly subtle and meticulous way.

Credits:

Featuring: Elisa Hampe

Curated by Robin Sara Stauder

Editor: Alice De Santis and Nicole Salotti

Visual: C41.eu @c41.eu