AT NIKE, INNOVATION RARELY STANDS STILL.

IT EXPANDS, ADAPTS, AND FINDS NEW AIR TO BREATHE.

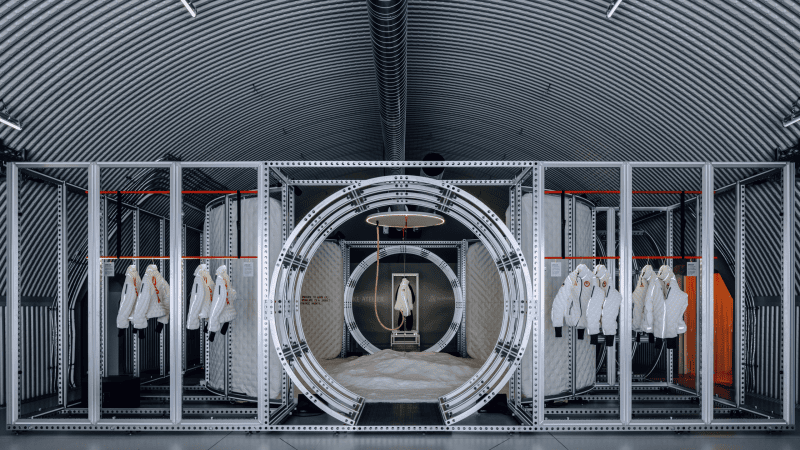

This ethos comes to life at Unlimited Air at Drop City, Milan, an immersive space celebrating Nike Air as a limitless platform for experimentation, where athlete insights are transformed into industry-defining innovations.

The Therma-FIT Air Milano Jacket is the latest expression of that philosophy—a piece engineered for the coldest worldwide stage and built from one of the brand’s most iconic elements: Air. Worn by Team USA’s elite athletes during winter medal ceremonies, the jacket reimagines insulation by using pressurized air as its core warmth system, delivering immediate heat in a silhouette that feels improbably light.

In this conversation, Martin Lotti, Nike Chief Design Officer and Danielle Kayembe, Expert Apparel Product Innovation Manager discuss the thinking behind Nike’s latest apparel innovations, from conceptual vision to technical execution. Together, they reflect on athlete-led design, the evolution of Air beyond footwear, and how performance, storytelling, and experimentation shape the future of Nike innovation.

ATHENA KUANG: I wanted to start with your background. You are the Chief Design Officer at Nike, with nearly 30 years shaping product, brand, and retail design across sport and lifestyle. At this point in your career, what part of the design process do you feel most connected to?

MARTIN LOTTI: It’s always been the same: the upfront process. Ideating, asking the “what if” questions. What could this be? What if we built X, Y, or Z?

It’s about creating a world almost two years before we release a product—envisioning everything from head to toe, including what the retail environment looks like and what the campaign looks like. The concept phase is where we allow ourselves to dream.

That said, it’s critical to execute. If it’s just a dream and athletes or consumers don’t enjoy it or see its value, it defeats the purpose. But the area I’m most excited about is definitely the upfront piece—the concepting of the project.

AK: Nike Air is both a technology and a cultural symbol. How do you approach designing for something that already lives in so many people’s lives?

ML: The process is always the same. It starts with the voice of the athlete. It starts with solving problems. That keeps us grounded.

We’re not trying to create a cultural icon. That’s an outcome, not a starting point. The Radical Air looks the way it does because it was designed for a specific purpose. It may be adopted by culture because it looks distinct, but that’s not where we begin.

We begin with questions like: How do you keep an athlete cool? How do you keep an athlete warm? That drives us toward a solution.

Does it stop with performance? No. We always say a good Nike product is performance, style, and soul—the combination of those three elements. We start with performance, then add style. Athletes from MJ to Serena have told me, “I play better if I look better.” And we ensure there’s a soulful element in the product as well.

In the Therma-FIT Air Milano Jacket jacket, for example, it’s highly technical. But inside, there’s rich storytelling for Team USA. There’s the Garden of the Gods mountain range—home of the U.S. team. If you look closely at the eagle graphic, the feathers contain a subtle victory sign.

That’s an example of leading with innovation while combining performance, style, and soul.

AK: The Therma-FIT Air Milano Jacket responds to the body in motion. Do you see design today as something that dictates more or listens more?

ML: I’ve seen both happen. Different projects lead to different solutions. I don’t want to limit our design team to one approach. I like entering through different doors and letting the best solution win.

AK: When a project like Nike Thermal-FIT Air starts, what is defined first: the product, the question, or the problem to solve?

ML: It usually begins with a question, because it starts with listening, with a capital L. Listening to athletes by asking questions. Listening through data in the Nike Research Lab. Listening to culture.

From there, we move into ideation—the dreaming process, the “what if” questions—and then quickly into prototyping, both digitally and physically.

As the world becomes more digital, we have to bring in craft. It’s a juxtaposition of high tech and high craft. The hand feel at the end of the day is incredibly important. We celebrate the human body and human potential, so we can’t lose that aspect.

If you follow the process through, it’s about building amazing products that are fully tested with athletes. It’s truly full circle—athletes at the beginning, during, and at the end of the process.

AK: Dropcity recreates extreme conditions. How close are these environments to the actual testing processes used during development?

ML: They’re central. We start with a specific environment. For Radical Air, we chose one of the most extreme environments: Western States—100-degree weather and an athlete running 100K. We intentionally pick an environmental challenge and say,

“If we can solve it here, it will work elsewhere.”

Those benefits translate. Think about the heat at the Australian Open in Melbourne—similar principles apply. The same goes for the Therma-FIT Air Milano Jacket: How do we keep athletes warm in Milan?

AK: In recent years, performance apparel has become more complex. How do you prevent innovation from becoming unnecessary complexity?

ML: This jacket next to us is the most complex garment we’ve ever built. Capturing air, enduring wash cycles — it’s incredibly difficult to execute. It sounds simple, but it’s not.

The consumer doesn’t need to see that complexity. In fact, the more complex the engineering, the simpler and more intuitive the solution must feel. You have to view it through the lens of the consumer, not the creator.

It’s about distilling to the essence. Good design isn’t about what you can add — it’s about what you can subtract.

AK: What part of the Therma-FIT Air Milano Jacket are most people unlikely to notice, but you consider essential?

ML: Most likely the interior — the lining, the storytelling, the discovery element. If someone notices the eagle’s feather detail and the hidden victory sign, they’ll realize we’ve thought about everything else too.

We did. And that’s the beauty of it. We go to the nth degree, whether it’s discovered or not. But it’s there to be discovered.

AK: How do you balance global consistency with local context, especially when presenting work in a city like Milan?

ML: It depends on the project. In the Serena project, it was deeply local — rooted in a specific place and story. Other projects need to be broader.

Most of the time, it’s better to narrowcast than broadcast. If you start broad, you risk creating something generic. At Nike, we usually start with the athlete. If it works for MJ or LeBron it will work for others. Narrowcast to broadcast is often the more intuitive route from a Nike design perspective.

AK: Inside Nike, how do you know when something truly represents progress, not just novelty?

ML: When it’s not just new, but new and better. In every design review, we ask:

Is it just different, or is it better? Did we help the athlete?

Sometimes progress is a substantial leap. Sometimes it’s evolution. Both are valid. But it has to move the product forward. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t deserve to go through the product creation process.

ATHENA KUANG: Innovation at Nike can feel very large. How do you keep the work grounded in the body and everyday movement?

DANIELLE KAYEMBE: Innovation is an area I find incredibly intriguing. At Nike, there’s strong alignment around centering the athlete and their insights. We don’t design things just because they look cool. We always ask:

What is essential for the athlete? What are we hearing from them? What is the pain point, and how can we remove distraction to improve performance?

That question drives everything we create. Even in team meetings, when reviewing new ideas, we ask: How does this help the athlete?

We also strive to be inclusive — whether that’s sizing or designing for different abilities. Athlete insight is always the foundation.

AK: Testing, failure, and prototyping are often hidden from the final narrative. Why is it important to show the process, not just results, today?

DK: This technology has evolved quickly in a short amount of time. But what’s equally important is that this isn’t the first inflatable jacket Nike has made. We have nearly 20 years of heritage exploring air in apparel.

Air is a core concept at Nike. We were so excited about the work that came out of this project that we wanted to share more of the process—the learnings, the experimentation, and honestly, the fun and passion behind it.

We’re geeks. And we know that many people who follow Nike—whether in outdoor, streetwear, or footwear—love the details. We do too.

AK: How do you translate extreme testing conditions (heat, pressure, airflow) into something intuitive for the body?

DK: That challenge was central to the work. We had to deeply understand those variables in order to build something that feels simple.

When we started, we didn’t have a framework for what “air” meant as a dynamic insulation system. We had made garments with inflation components before, but we had never explored air as the core form of insulation.

We worked closely with the Nike Sports Research Lab. They have heating and cooling chambers and advanced temperature-control systems. Together, we developed tests to simulate conditions in Milan and understand how an athlete’s body would respond.

We also conducted 380 hours of wear testing in Colorado in December. Athletes hiked, biked, skied, snowboarded, and took the jackets into extreme mountain conditions. We gathered every jacket back and used that feedback to refine the design.

You’ll notice different baffle heights throughout the garment. Under the arms, there’s no air— just fabric—to allow mobility. If there’s air everywhere, you become the Michelin Man and can’t move. That insight came directly from athletes. We made the process highly iterative, incorporating feedback at every step.

AK: As a product innovation manager, you work between imagination and feasibility. Where do the most productive tensions happen?

DK: The way I like to work is to start very broad. At the beginning of this project, we gave ourselves room to explore and imagine freely. We went wide in our experimentation, which created a rich pool of inspiration once we began narrowing and focusing.

That early openness made the final direction stronger.

AK: Air is often read as identity at Nike. How do you balance emotional expression, performance, and community?

DK: Nike is such an iconic symbol, and our athletes are not one-dimensional. We value that complexity and want to create apparel that reflects it.

Performance is always the core. If a product doesn’t improve something—sweat management, temperature regulation, mobility—we won’t make it. It has to remove distractions and enhance performance.

At the same time, we recognize the psychological factor. Appearance drives confidence. If you look good and feel good, you play better. We design with all of that in mind:

Performance, Expression, Confidence.

AK: With Nike Therma-FIT Air Milano specifically, what aspects of the jacket’s performance are most important to experience in person?

DK: This project grounds new exploration in Nike’s heritage—particularly our legacy in footwear and air technology.

Radical Air explores air as cooling. The Therma-FIT Air Milano Jacket explores air as warmth. It’s a fresh take on something people think they already understand.

Many people have only seen photos. Some have even said the Therma-FIT Air Milano Jacket looks like a golf ball and must be hard. But when they touch it, they’re surprised—it feels like a pillow. It’s incredibly soft and lighter than any jacket you’ve worn, yet the warmth is immediate.

That physical experience can’t be translated through an image. People need to see it, touch it, and understand how it was built.

AK: What part of Nike’s innovation process would surprise people most?

DK: How much fun we have.

The Therma-FIT Air Milano Jacket team was incredibly passionate, and we genuinely enjoyed the exploration. Early on, we made all kinds of experimental versions—oversized jackets, mismatched colors, fully transparent shells. We created a clear version with a visible air-channel system. Some ideas worked. Some looked wild. But the experimentation was the fun part.

Our floor also houses other innovation teams—footwear, the space kitchen—and we constantly exchange ideas. I called the footwear innovation team early on and showed them our prototypes. They sent over materials they were testing, including colored foam beads we could use inside a transparent jacket. We geek out together.

We text each other on weekends about new pumps for camping, self-inflating motorcycle jackets, or emerging technologies. We genuinely love this stuff.

WE’RE GEEKS—AND WE’RE PROUD OF IT.