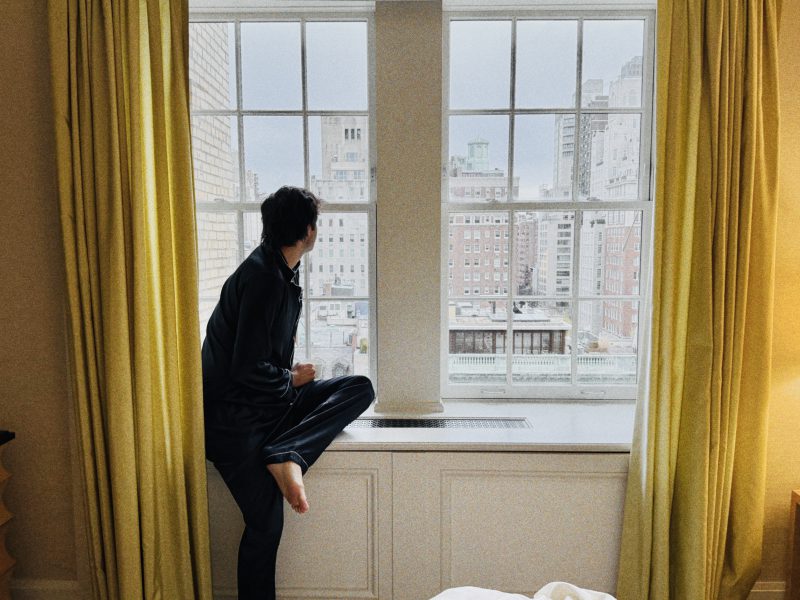

On a Sunday morning, when the light over the Upper East Side turns gauzy and forgiving, the windows at The Mark Hotel are best left slightly ajar. From Madison Avenue comes the low, habitual murmur of traffic — a polite buzzing — while a ribbon of air slips in from Central Park, carrying the faint scent of wet leaves and coffee. The light is soft, luminous, almost powdered, the kind that makes the limestone façades across the street appear momentarily cinematic. In those early hours, The Mark does not feel like a hotel so much as a neighbor: the well-dressed one who has lived on the block for decades, who nods hello, who remembers your name.

In New York, where excellence is baseline currency, The Mark excels not through spectacle but through familiarity. This year marks a century since its first iteration opened its doors, and in that time it has become less an address than an institution — part pied-à-terre, part discreet clubhouse. Staying here, even for a single night, invites a kind of temporary citizenship. You begin, almost unconsciously, to develop a routine.

It might start with coffee taken downstairs before the avenue fully stirs, or with a brisk walk along the park’s edge, returning to the hotel’s calm geometry. Reimagined in 2005 by the French designer Jacques Grange, the interiors exemplify a particular strain of New York refinement — one that makes early-2000s design feel not dated but definitive. Grange preserved the building’s landmark dignity while infusing it with a high-French sensibility: bold black-and-white floors, lacquered surfaces, sculptural lighting that glows rather than glares.

He enlisted a circle of creative luminaries — Karl Lagerfeld, Guy de Rougemont, Paul Mathieu and Mattia Bonetti among them — to contribute bespoke furnishings. The result is a study in contrasts: striking contemporary lines softened by upholstered comfort, a certain Parisian hauteur tempered by American ease. In the rooms, the palette remains crisp and disciplined, yet never austere. One feels both hosted and at home.

Downstairs, routine turns social. Breakfast might yield to lunch at The Mark Restaurant by Jean-Georges, where the menu balances uptown polish with downtown appetite. By evening, the bar fills with a cross-section of Manhattan: gallery owners, discreet celebrities, mothers still in tennis whites, editors preparing for Monday.

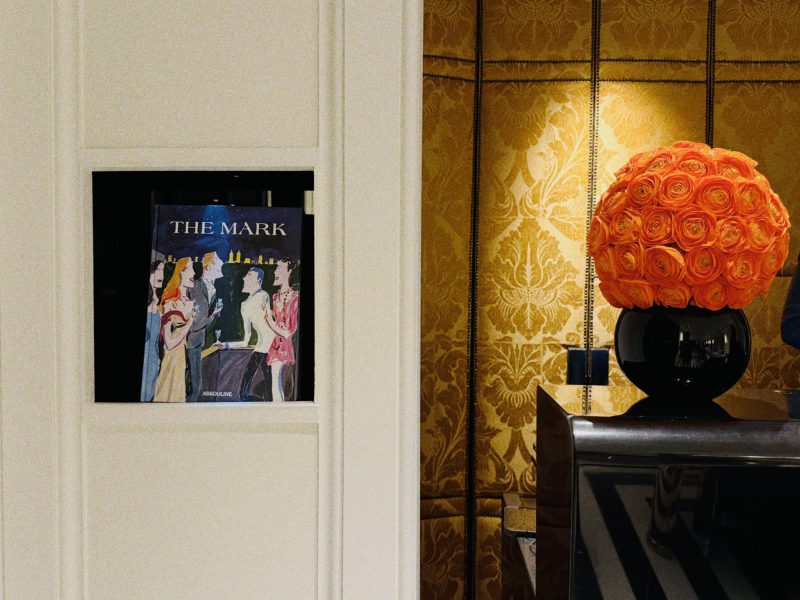

There is grooming at the Frédéric Fekkai Salon, browsing at the Assouline bookshop, and, should one require it, a pedicab — the so-called “Bergdorf Goodman Express” — idling curbside. Culture, gastronomy, exercise, and society orbit within a few blocks: museums along Fifth Avenue, boutiques on Madison, the green lung of the park. It is possible, if one is disciplined, never to venture far. The hotel contains a curated version of Manhattan; the city, in turn, feels arranged around it.

Throughout the years, The Mark has also served as the unofficial headquarters of the Met Gala — fashion’s most scrutinized night — its suites transformed into ateliers of tulle and tailoring. North America’s largest penthouse crowns the building, a theatrical aerie that embodies the hotel’s “boldly lavish” ethos without surrendering its discretion. It is a place where spectacle is rehearsed privately before being released into the flashbulb storm.

That tension between privacy and performance is elegantly documented in the new Assouline volume, The Mark, written by Derek C. Blasberg. Part coffee-table objet, part insider chronicle, the book traces two decades since the hotel’s reimagination, weaving together archival imagery, influential personalities, and intimate anecdotes. Flipping through its glossy pages in the Assouline corner downstairs, one recognizes the through line: The Mark is less about transient stays than about accumulated moments.

“People come to The Mark because they know it’s more than just a hotel,” its owner, Izak Senbahar, has said. “It’s a place that makes for unforgettable memories.” Spend even 24 hours here and the sentiment resonates. You fall into step with the neighborhood’s cadence, adopt its rituals, greet the doorman as though you have always done so. When you finally close the windows against the evening hum of Madison Avenue, the city feels not overwhelming but proximate — intimate, even.

Like the newsstand vendor who hands you your paper without asking, or the barista who begins your order before you speak, The Mark offers the rare luxury of recognition. In a metropolis built on velocity, that may be its most enduring indulgence of all.