Nifemi Marcus-Bello’s work fits into the relatively new current of design that investigates the space in between the production of single pieces and that of small series. Marcus’ work has strong cultural roots that take shape, from time to time, in objects that the designer uses as vectors of strong meanings. Almost always single-material, his collections come to life thanks to a deep knowledge of materials and related processing techniques, in which the craftsmanship character is not only a tool but a kind of amplifier of design messages. We interviewed Nifemi Marcus-Bello to try to better understand his method, his approach to the design of his collections, and what he thinks it means today to convey meanings and stories through objects.

Tommaso Caldera: Would you please start telling us about your background?

Nifemi Marcus-Bello: I studied product design for my undergrad and master’s at the University of Leeds. I am a maker at heart and started making at the age of 13 and haven’t looked back since.

TC: When and how you decide to start with your own activity?

NMB: I decided to start my own practice after having a great deal of questions and thoughts about what contemporary Lagos or West Africa should look and feel like. With the idea of creating contextual designs from a material, human, and sustainable perspective.

TC: How would you describe your practice?

NMB: My practice is split into two, there’s a commercial side and an artistic side. The commercial side is sometimes dedicated to client and collaborative work, creating design or creative solutions for various brands and private clients, it can go from a piece of furniture to an actual physical product. The artistic side to the practice is more of me carrying out investigations around materiality, production techniques, and identity in the hopes of creating objects, forms, and experiences dictated and driven by my findings.

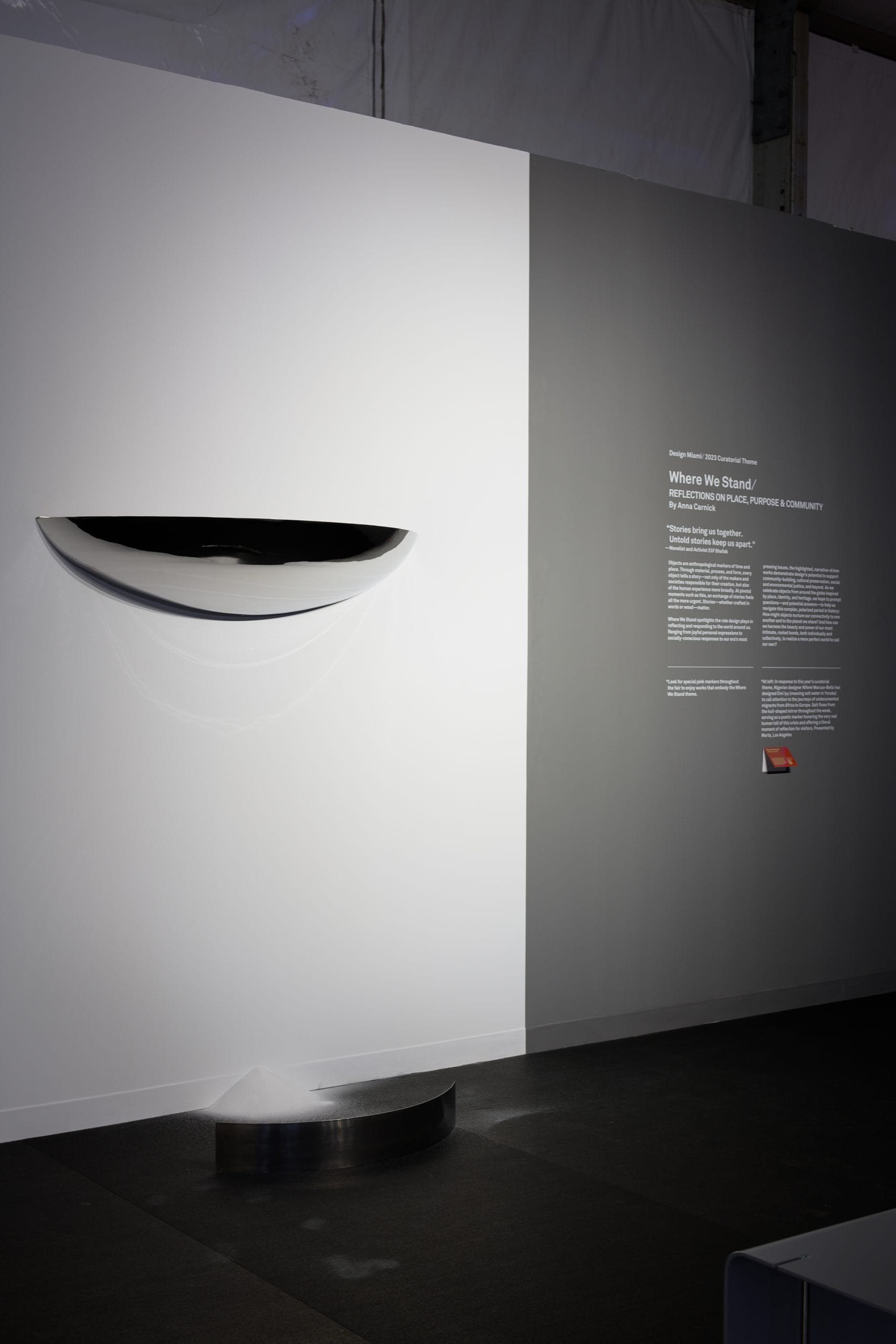

TC: Your installation “Omi Iyo” has been installed at the entrance of Design Miami 2023. Would you tell us about this project?

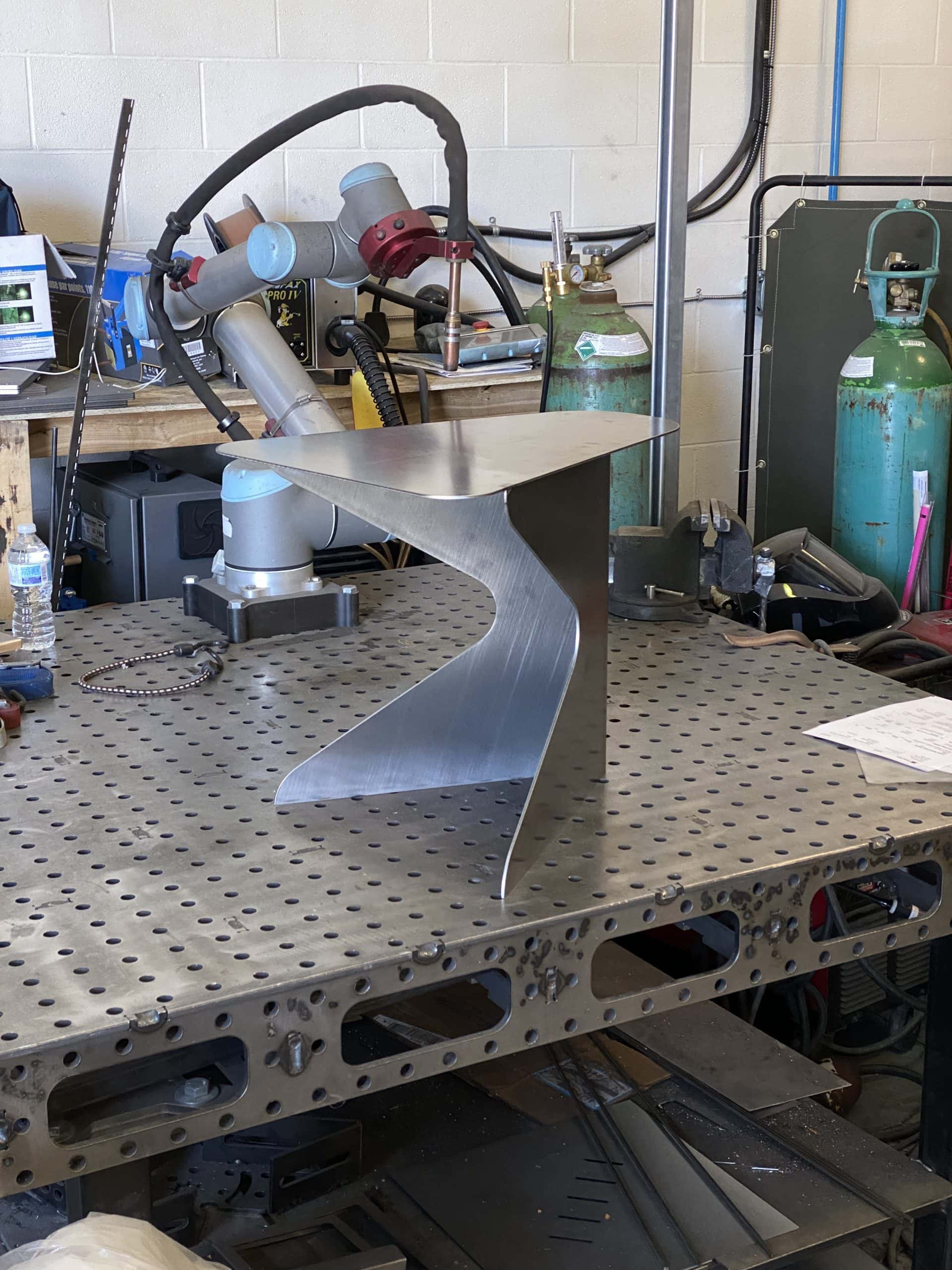

NMB: Omi Iyo (translated as “Salt Water” in Yoruba) was made in response to the journey of undocumented migrants from Africa to Europe. The work references references to the hull of a boat, the primary mode of transport.

The polished stainless steel work—though appearing as a solid mass—is hollow and filled with salt that, over the course of the Fair’s five-day program, flowed continuously to the ground from a small opening at the sculpture’s base, resulting in a self-patterning heap of crystals beneath the work.

The salt is symbolic of the Atlantic Ocean, which has to be crossed from the Global South to the Global North; and of its chemical composition, as well as the physical treachery it poses to the immigrants who travel across it in dangerously inadequate and frequently overcrowded vessels. As a mineral that is essential to the human body’s function (fluid balance; the regulation of the nervous and muscular systems), salt is also emblematic of existence: of the individuals who risk the journey towards a better life but whose personages—faces, stories, and experiences—have been obfuscated by circumstance. In this, the ‘salting of the earth’ also signifies the socio-economic and systemic hardship which those migrants aspire to leave behind them.

TC: There’s a series of pieces I’d like to know something more about Oriki ACT1 and ACT2. How did you come up with the idea of creating these two collections?

NMB: The Oriki design series is an investigation around materiality, production techniques, and identity, with my findings I am creating objects that act as some sort of archive system for these manufacturing techniques and findings. ACT 1 was an investigation and collaboration into bronze casting in Benin and what it meant or looked like to introduce new-age materials into a production technique. ACT2 was looking into how globalisation and consumption in the global North affects and starting to dictate materiality in the global South.

TC: What do you like about working with metal as the main material for your pieces?

NMB: As a maker, metal was the first material I interacted with and it so happens that it was the first material I also found contextually in Lagos when investigating indigenous manufacturers. I like the ability for it to take new forms if respected and understood.

TC: I’m curious to know something more about your design method. What’s your starting point? The material, the function, the concept?

NMB: The context and the concept. The first step is always to contextualise the idea from a material, human, sustainable and geographical standpoint while generating the concept. So that when executing all of these parameters have been considered, understood, and respected. Then I think the ideas flow much easier and healthier.

TC: Do you think that’s always possible to convey meanings using objects?

NMB: Objects exist for a reason and in Africa, it can be physical, spiritual or emotional. And I think now more than ever objects have to convey meaning or spark a dialogue and go beyond functionality, even if the message is one of “sustainability”.

TC: Collectible Design is a decline of Product Design that is grown more and more during last years. What do you think is the reason of this growth?

NMB: I think product design got a bit cold and lost a lot of human touch, look and feel to it. I think people want to have emotional connections to products and not feel like a part of a simulation.

TC: What do you think are the main differences, in terms of language and aesthetics, between collectible pieces and industrial design pieces?

NMB: I am interested in the answer to this question, I have only just started my journey into collectible pieces and for the reason was that some of these ideas that I was looking to explore just can’t be mass-produced and I had and still have burning questions around these themes I am exploring. I think I might have an answer in a few years but right now maybe this is what I am also searching for.

TC: Can you tell us something about upcoming projects?

NMB: I have plenty of projects and project launches this year and a few collaborations in the works. My first museum show will open soon at the Stedelijk Museum in the Netherlands.